A honey bee colony is a superorganism. Something I say very often is: “A colony is more than the sum of the number of adult bees and brood cells!”. That seems difficult to understand sometimes. Considering that honey bee health is getting more attention, however, this is an important concept to figure out. Even more so, if we go a step further and speak of welfare of honey bees. My interest in this started several years ago, when a colleague asked me to give a lesson on the subject.

The term “superorganism” isn’t easy to define. As far as I know, Hölldobler and Wilson introduced it to describe why social insects are special and fascinating. Why we have to see the colony as a whole, not the individual bees (or ants or any other social insect). A superorganism, in very poor words, is a self-organising entity. The queen and drones have the monopole on reproduction. They need the workers for brood rearing, foraging, cleaning, etc. A single bee doesn’t display the whole range of behaviour of the species and it’s not able to survive without the colony.

Superorganism and welfare – unifying two concepts

The welfare concept, on the other hand, usually deals with vertebrate animals. Mammals and birds mainly, but the OIE lately also introduced an aquatic code, dealing with fish. Insects are still missing, though some of them are managed. For honey bees, the welfare discussion is becoming louder. In the past two years, I’ve been asked more often to give talks or write something about the subject.

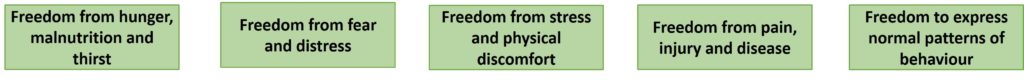

In the book “The Welfare of Invertebrate Animals“, my colleague Antonio Nanetti and I tried to unify the concepts of superorganism and welfare. The OIE defines welfare with the “five freedoms”:

The freedom of diseases is only a little part of the whole concept. It also shows the connections to the management by the beekeeper, like the freedom to express normal patterns of behaviour. The discussion on negative effects of pesticides on honey bees (as managed animals) touches welfare aspects, like the freedom of stress, pain, or distress. These are effects that endanger the integrity of the superorganism. Everything linked to sublethal effects can be discussed under the welfare aspect, though usually this word doesn’t appear in the discussions.

Nutrition is an overarching factor

Nutrition affects many aspects of the welfare of the superorganism. First of all, of course, it touches the first freedom: of hunger, malnutrition and thirst. Besides the obvious need to eat on the individual basis, there’s also the nutrition of the colony (i.e. the superorganism). The pollen and honey provisions of a colony make them survive cold winters or periods with bad weather. The amount of brood varies with the availability of pollen and nectar (hence the brood stop in winter). There are feedbacks between the nutritional state of nurse bees, the larvae and the health of the colony in the following generation.

In the past years, it became clear how important biodiversity is in this context. A “healthy diet” for bees (managed and non-managed) is diverse. If a honey bee colony can feed on various different pollen sources, they show better winter survival and are more resistant to diseases and even to varroa mites.

Here, we also have again a link to the One Health concept: Flowers act like “dirty doorknobs“, the place other insects get infected, too. On the other hand, pollinator diversity helps to “dilute” these infections – which again helps honey bee welfare. You see, this is a network, a complex picture.

Management and its challenges

The superorganism honey bee colony is quite forgiving, it can cope with suboptimal conditions for a while. This is both positive and negative. Positive, because beginners in beekeeping get the opportunity to learn – without immediately killing a colony after a mistake. And, obviously, because the environmental conditions aren’t always optimal. However, this also means that a beekeeper gets used to this plasticity. “I always did it like that and it was always fine.” Yes, maybe.

But like with other complex systems there is a tipping point. If bad management comes together with an insufficient flower supply, high parasite load, and maybe also pesticide exposure the system collapses. Too many adverse factors together become the last straw that breaks the camel’s back.

We are in such a situation at this moment: we stand in front of honey bee colony losses, insect decline, pollination crisis and whatever. Now, we have to address the problem as a whole and not focus only on this last straw.

Welfare as a holistic approach

Welfare refers to managed animals. Management brings additional challenges, especially with honey bees. Insects don’t show their well-being, fear or stress in a way that’s easy to understand for us. Another sentence I say quite often is “Honey bees, not honey machines” when talking with beekeepers. It often is a matter of experience and the willingness to learn and see the signs. And maybe change something you’ve “always done that way”.

Management means taking away their food provisions (honey), breaking up the nest during the controls, putting combs in different positions, stressing the bees by too much smoke or by not taking care of crushing bees. Beekeeping is more about the beekeeper’s needs than the bees’ ones. The fifth freedom, “of showing natural behaviour”, is always the most difficult one. In managed animals, be it honey bees or cattle, there’s always a compromise. There’s a “purpose” (honey harvest, pollination services etc.), they need to cover a human need as well. However, beekeepers profit if they try their best to respect their colonies’ needs as well.

By not harvesting every last drop of honey. By taking care of the conditions while transporting them to other places. Shortly: By respecting good practices.

Good practices for superorganism welfare

It’s time that good practices get established in beekeeping with a more solid foundation. There are great beekeepers, I’d say many. But there are also those who don’t care at all. This is mainly an educational problem, the missing knowledge transfer from science to beekeepers and also the very human tendency to focus on the most obvious. However, I think it’s most important to address the issues faced by honey bees and beekeepers in a more holistic approach.

Beekeeping is very diverse around the world. Yet, I think that we could develop a basic toolbox of what good beekeeping practices are, that can be adapted to the different conditions. This includes also talking to farmers, veterinarians and those who want to “save the bees”. It’s about communicating the complexity and finding common solutions. Honey bees (and also other managed bee species) need to be included in the global strategy of the OIE.

One thing that distresses me is seeing bee yards sitting in the middle of a field in the blazing sun without shade being provided. I think it is cruel.

Hi Judy, thank you for your comment. You’re right, chosing the right site for the apiary is very important. Leaving them exposed to the sun like this absolutely doesn’t respect bee biology – they’re forest animals after all. Their natural caves would protect them from direct sun. This is also something that’s quite easy to respect. As I mention in my post, I think it’s mainly an educational issue. People see insects as little automats, but we have more and more evidence that this is not true. Let’s spread the word!

yes it is i think they should provide some shade

That’s part of good practices, but unfortunately, some beekeepers don’t respect it.

To tell the truth, I am so glad that I came across your article because I really like being engaged in studying bees because I think that they perform a really important function not only in our nature, but also in the whole world. After reading your article, I came to the conclusion that honey bees are exceptionally developed insects that take part in a variety of complex tasks. Of course, a great deal of factors affect the welfare of the superorganism and it is really important to take them into account in order to see bees healthy. It is so sad that we stand in front of honey bee colony losses because it indicates that we are moving in the wrong direction and we need to reconsider our attitude to living organisms which are an inevitable part of our nature. I think that it is essential to fight with the current situation and take all necessary measures to fix it, striving for getting rid of all unfavorable factors, otherwise, this will escalate.

Hi Marina, thank you for your feedback. The matter of welfare for managed honey bee colonies is getting stronger since I wrote this article. At least in the practice of beekeepers and vets. We’re obviously still not there (as we aren’t with other managed animals), but I see it as a very promising beginning of an important development. I will surely continue writing about the subject!

How does understanding the plasticity of honey bee colonies contribute to effective beekeeping practices?

Well, beekeepers – and people in general – like to say “I always do it like that…”. They treat honey bee colonies like little honey machines. So knowing about plasticity may open the door of observation. And by that, better practices. Biology isn’t linear, doesn’t follow a clear “if this then that” scheme very often. Observation and the knowledge of plasticity helps to adapt to different conditions and act better.