In a very influential paper, Dr. Peter Rosenkranz and colleagues talked about “hard and soft varroa treatments”. This was often misunderstood as related to the efficacy of the respective substances and created the completely opposite effect of what was intended. This may be an example of how the attempt to make things easier to understand sometimes goes completely wrong. Maybe also an example of how important it is to really listen or read and not to interpret too fast.

For many, “hard varroa treatments” (the synthetic ones) meant that it was hard on the mites, so killed a lot of them. “Soft”, i.e. treatments based on organic substances, on the other hand for many sounded as if this was a feeble attempt to get rid of the mites. But nothing that could really help. Maybe as a measure in between. This opinion was especially common in some countries and much less in others. Here in Germany, for instance, with a great percentage of hobby beekeepers, this doubt didn’t come up. Another factor may have been the many bee institutes. They have a strong connection to the associations and there were a lot of training sessions after developing the organic treatments. Most German beekeepers use formic acid in summer and oxalic acid in winter.

It’s different in countries with more professional beekeepers. Here, mainly because of time constraints, the quick and easy strip solutions are more popular. But this isn’t the only reason. For instance, I know professional beekeepers in Italy who successfully treat with oxalic acid in summer – queen caging included. Even with the large number of colonies you need to live from beekeeping alone. So, it’s also a matter of organization. And training. If you need some basics on how to decide on varroacides, I wrote about a strategy some time ago. Check it out. The myth about “hard and soft” came up in South America, as far as I know. This situation also shows how important it is to collaborate. More on that later.

What “hard and soft varroa treatments” really means

But back to “hard and soft varroa treatments”. The thought behind this wording was completely different. It was actually about hard or soft impact on the bees. Let that sink in.

You may have heard it already: Every medicine (veterinary or not for that matter) not only has an effect, but also side effects. During the registration process, the most important question is whether the benefits are larger than the risks.

This is the case for the registered varroa treatments. There are side effects, but if you treat correctly, i.e. according to the label, you will kill the mites without noticeable effects for the bees. Some side effects, may be deemed much less dangerous than the risk of the parasite. So, even if you see agitated colonies after a treatment, this isn’t as bad as losing the colony to varroa. Especially as the agitation is transitory.

But we can go a step further: Thinking also about long-term effects like residues or resistance against the substance in question. And here’s where “hard and soft” comes in. “Hard” varroacides, i.e. those with synthetic active substances, have a higher risk of residues and resistance than “soft” ones. This is what Rosenkranz and colleagues wanted to express with their classification.

Availability of varroacides

I hope it became clear that you can treat safely with “soft varroa treatments”. They do kill the mites, sometimes even better than the “hard” ones. Read the paper yourself to get the details. I also wrote a bit more on what to know about varroacides, if you need a refresher on that.

Independent of how you call them, for having varroa mites under control, it’s important to have them available to you. Especially, to avoid illegal use and make sure veterinary medicine is used correctly. For that, the paper I discussed last week is really helpful: In a big table, the authors summarized the information of the different varroacides we have and how available they are (legally) in different parts of the world.

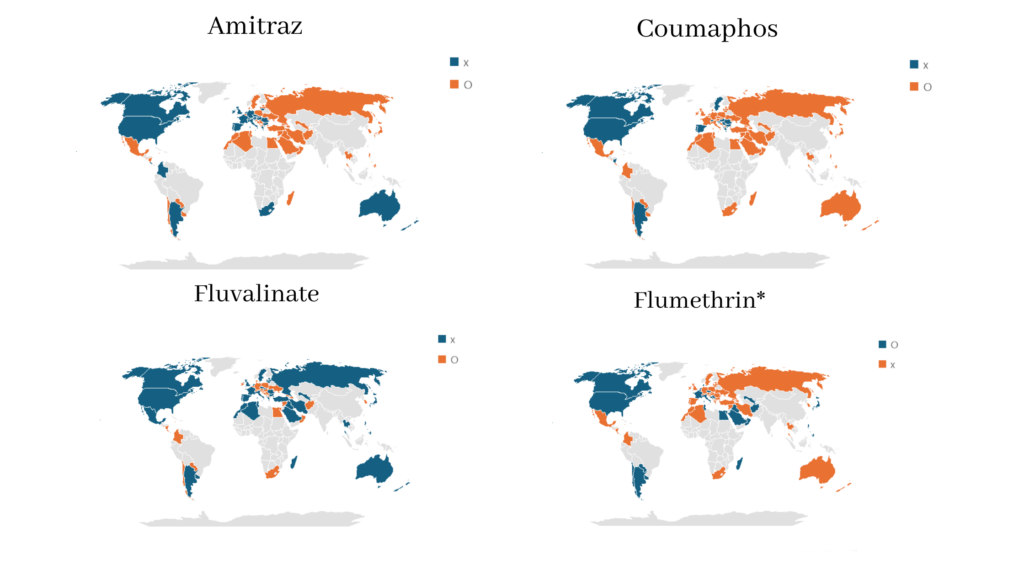

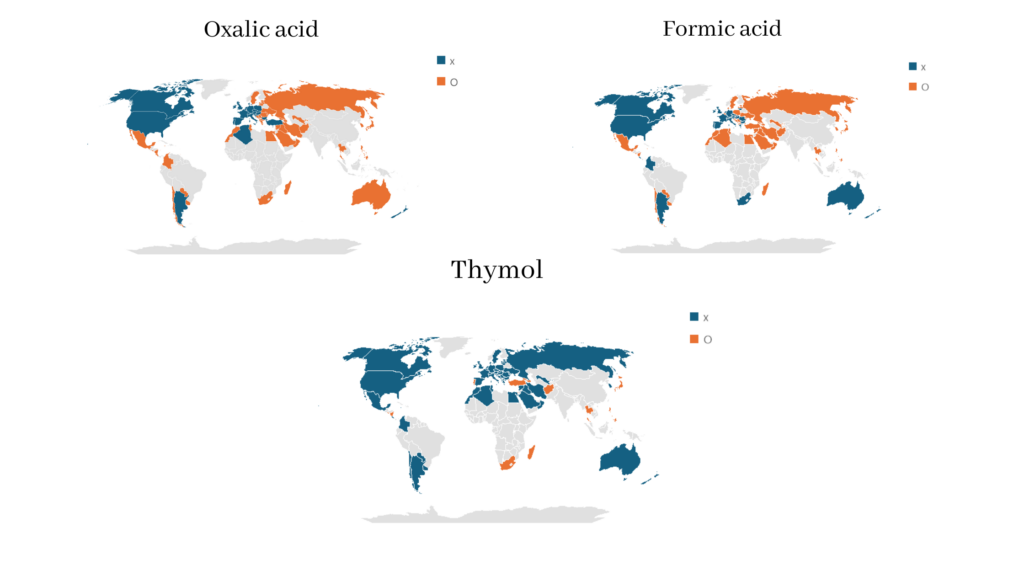

I made some maps out of this and corrected some misunderstandings and mistakes I noticed. However, the important thing: We don’t have much information on many countries. Which is bad. That doesn’t mean that there are no problems with varroa (at least not always), but that there’s no real framework for beekeepers to act upon. And that carries all the problems of illegal treatments.

Availability of synthetic (i.e. “hard”) varroa treatments in different countries all over the world. Blue means that the substance is available in that country. Orange are the countries where the respective substance isn’t available. And, finally, grey are those countries we don’t have information – or no varroacide may be registered at all. Map according to the data in Jack & Ellis (2021), with some corrections where I knew it’s a mistake. EDIT: Flumethrin has been heavily used in Australia since varroa appeared there in 2022 according to the editor of the Australasian Beekeeping Magazin, Kris Fricke.

Map of the availability of varroacides with active substances of natural origin (aka “soft”). The colours and the disclaimer are the same as for the synthetic substances. As you can see, thymol is the most common one – despite oxalic acid being the most efficient substance we have currently. Australia, rethink that! (If this info is correct…). EDIT: As Kris Fricke from the Australasian Beekeeping Magazin told me, oxalic acid got the marketing permission in November 2024. I didn’t include hop beta acids, which are registered only in North America. The EU had doubts about the safety for the treated animal, i.e. honey bee colonies with these substances.

In many countries there are only very limited options. Maybe only one or two substances that are registered. This increases the risk of illegal treatments, resistance, etc. Beekeepers aren’t isolated, most of them know how to use social media. They will take up every “tip” they could get their hands on and what seems doable. So, a legal framework is extremely important. And education. As always. To limit the rumours and pass along good information.

The three levels of responsibility

Keeping their honey bee colonies healthy, is first of all the responsibility of the beekeeper. However, if you leave them alone, they can’t take this responsibility. They can’t know things, if nobody ever tells them. This applies also to varroa treatments and varroa itself. To deal with an issue, you need to have the right tools. And you have to learn about them. Remember the situation in Germany and the good collaboration between beekeeping associations and bee institutes?

Here’s where the “three levels of responsibility” come in, how I like to call it:

- The individual level. This is the beekeeper who has to respect good practices, use legal treatments, stay informed. This level is the most visible, the one which will always get blamed if something goes wrong. On the other hand, the next two levels carry great parts of the responsibility as well.

- The community level. This includes everything from small groups of beekeepers who discuss their common problems to large training programs by associations. Or courses at the bee institutes. We’re social animals, so the first step usually is to ask somebody else for advice. The one who’s asked – be it a neighbour, an association, or a scientist – has the responsibility to give the best advice possible.

- The political level. Yes, politics. This is the level who has to give the framework the other levels have to follow. So, by making good varroa treatments accessible, for instance. With a serious registration process. By allocating money for training and consulting, as well as applied science.

All of these levels interact with each other. However, in my opinion, the community level is the most powerful. I’ve seen active associations do a lot for good practices. Both in countries with a mostly hobbyists or with a lot of professional beekeepers. Or many or little bee institutes. While inactive associations only fed a sense of helplessness and mistrust. The community level can also build up the necessary pressure for politics to take up their responsibilities. Being in between is an uncomfortable position, but also a very crucial one.

Everyone doing their part

However, the individual beekeeper has to open up for the collaboration at the community level. Talk openly about his problems, so that others can help him. Give him the tools he needs. Not stay at the level “scientists and vets don’t know about my practice”. Tell them. That helps. Same is true for scientists or vets, obviously. They have to open up and listen to beekeepers. Also, policy makers need to think further than only in the administration period they’re in. Really try to take their responsibility and give this framework they have to care for. And keep it current…

So, to be honest, I don’t care about wording like “hard and soft varroa treatment”, “natural or synthetic”, or what other buzz word is currently “hip”. Words can be just empty vessels if the meaning, the responsibility, behind them is missing. What I care about is everyone doing their part. To get ahead.

How does that proverb go? If you want to go quick, go alone. But if you want to go far, go with others. I surely butchered it. But you may get what I intend to say. This is good advice in general. But my area of expertise is bee health, so I talk about that. And it applies perfectly.