Last week Science published a study about the manmade dispersal of Deformed Wing Virus (DWV). This virus alone causes asymptomatic infections, but in association with Varroa destructor, it becomes a clinical disease closely related to winter losses of honeybees. The parasites are vectors for the virus and only together they cause symptoms like crippled wings and shorter abdomens. There were three especially interesting issues in this publication:

- The spread of DWV follows the spread of varroa mites. The phylogeographic analysis performed by Wilfert and co-authors demonstrates this association. Varroa introduction in Hawaii and New Zealand were followed by higher prevalence of DWV and increased viral loads.

- DWV originates from European honeybees and was transmitted to its parasitic mite, V. destructor. The latter, therefore, is a new host for the virus.

- Trade and movement of honeybee colonies drives epidemic growth of DWV and by this, the virus became also a threat for bumblebees and other wild pollinators

Reading the paper, I had to think of other manmade threats to bees. Varroa itself is a well-known example: there are many stories and suspicious facts of who brought this pest to Europe. Several scientists are blamed for this. Maybe. Scientists are not the better class of human beings, there are all sorts of them as in every other group. But I wonder if such accusations help. Considering that Varroa mites now have spread worldwide, it is difficult to blame single persons. It may be mostly again due to bee transports, also to places where European honeybees are not native. The problem is much more complex than single researchers not thinking of the consequences of their acts. There is an interesting graph in this paper, showing where and V. destructor has been detected on Apis mellifera: the oldest record is from the 1900s in Indonesia. The massive dipersal though begins in the 1960s. Only Australia manages until now to keep the territory free of varroa mites. And for large areas in Africa no data are available.

Parasites profit from lack of awareness

The paper from Wilfert et al. is commented by Ethel Villalobos with a very striking note: “The mite that jumped, the bee that travelled, the disease that followed”. This title condenses a very long story. The Europeans bringing their bees to Asia did not think about potential risks, they just wanted to have the bees they were used to. They did not take into consideration that parasites and diseases could change hosts. Environmental awareness was not as common as it is today. This is no excuse, just an explanation. But in my opinion, nowadays we are much more to blame. Environmental awareness is not as common as it should be with all the sources of information available for everyone. But much more important is the fact that we obviously do not learn from our mistakes. We still introduce foreign species without thinking. Worse: thinking only of our own interest. Parasites profit from this narrow-mindedness.

The latest case may be the introduction of the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina tumida) to Southern Italy. It seems that the situation is under control, though there are still positive apiaries found. But in any case it is not as devastating as feared or reported from the US. A. tumida may be an argument for another post, in this context it is another confirmation of what I said about V. destructor before: there was a single or a group of persons who thought that they were importing better bees than those they had. And did not care about the regulation and the ban of bee imports to Europe from countries with the Small Hive Beetle. Perhaps they did not know, most probably though they just did not care. In 2004, A. tumida was detected in Portugal, fortunately in time to avoid that the beetles could spread. I am quite sure (without any sign or proof) that also in Germany, UK, Poland or other countries in Europe beekeepers import bees from Australia or the US despite of the ban. Who knows why. They are just lucky that the conditions in their countries are not suitable for this pest. Instead of blaming beekeepers, scientists, politicians or who ever else, we should think of what we can do to implement and control useful and reasonable rules.

A wider context

Let us have a look at the third point of the list above: Trade and movement of honeybee colonies drives epidemic growth of DWV and transmit this virus to other pollinators. There is already evidence that DWV has an impact on bumblebee survival. DWV has been found also in other bee species, like Andrena spp. (Mining Bees) which are important pollinators also in fruit orchards like apples. There is less evidence about the effects in these species, but if DWV is able to replicate in Varroa mites, why should it not in solitary bees? These are closer related to the original host, A. mellifera than the parasite is. There is work to do and in fact, knowing and understanding the diseases of pollinators is one of the key questions in research.

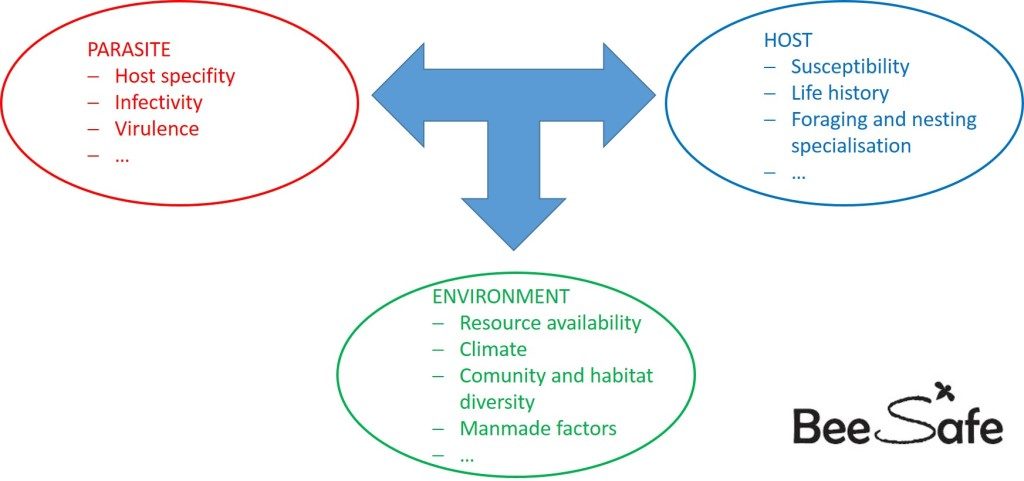

To add another detail to the puzzle: as Graystock et al. published last year, parasites can be transmitted on flowers. After infested pollinators visited a flower, their parasites (Nosema ceranae, N. apis, N. bombi, Critidia bombi and Apicystis bombi) could be found on these flowers. By this, they became vectors for the parasites that were transmitted to other species. Bad enough. To this adds a very important point: parasites and hosts, both are part of a complex environment. With this publication we have at least a cue about the role of flowers in this story, but there are other factors: climate change, resource availability and diversity and many more. In the DWV paper above, the authors stress that the threat may have become more severe also because of ecological changes. To name one: agricultural landscape, actually, often is a desert for bees. To the most discussed impact by pesticides, also habitat loss, low foraging and nesting resources and other factors may influence the pollinator-parasite relationship.

Making a complicated story short -relationships in a host-parasite system

And if we now look again at the list of parasites that Graystock et al. studied: there is Apocystis bombi, a main suspect for the decline and supersedure of Bombus dahlbomii by B. terrestris. So at the end, I am coming always back to my “favourite” issue in the past weeks, introduction of alien species. All this information we already have, should make us extremely careful before manipulating our environment. Nothing is as constant as change, I began this blog discussing this. But prudency would help.