Our land use is a reason for concern: with the increasing human population on earth, we’re claiming more and more of it. We use it to build houses, streets – and to produce our food on it. With all those humans needing food, crop production has focussed on maximizing yields. This has caused undeniable problems. In many aspects, we’re shooting ourselves in the foot. However, since reading about why most pollinator conservation programs fail, I’ve been thinking differently about solutions.

My father used to say that it’s easy to blame if you’re not responsible for finding a solution. It’s easy to blame farmers for using pesticides. But banning all pesticides won’t save the bees, the world and not even ourselves. Because the root of the problem is something else: we’re simplifying. The landscape in this case. When thinking only of productivity, hedges, earth paths, wasteland, and other habitat become unnecessary. The result is a monotonous landscape. Already during my university times in the 1990s, we talked about the “farmland desert” (though deserts can be highly diverse, but that’s not today’s topic). Farmers are doing what they’re asked to – they produce huge amounts of cheap food. If we want to change something, we need to offer an alternative.

Our land use creates a lack of habitat

But why is it a problem for biodiversity when the landscape is monotonous? Very simple: because every little structure in a landscape is habitat. A hedge, for instance, is home for many species. Cutting it down means destroying this home. Insects, birds and other wildlife may find similar hedges nearby, but fewer hedges also mean less space and food for them. Hedge-inhabitants will get less abundant and some species will disappear. Because they needed exactly the conditions of hedge A, which hedge B doesn’t offer. Specialists like this are most vulnerable. By losing habitat, the diversity goes down.

We have two components of diversity here: the species richness (i.e. number of species) and the abundance of individuals in every species. There’s also the aspect of dominance or evenness, meaning that some species are common and abundant, you see them always and everywhere. Other species are rare and less abundant. The more dominant single species are, the higher the “evenness” of a community. For instance, I’ve been at places at which 90% of the bees I saw were common carder bees (Bombus pascuorum). Many of them. From time to time some other bumblebee or honey bee, very few solitary bees. These were bee communities with high evenness. If you just looked at “bees” you could say everything was okay. But this wasn’t a diverse bee community.

The vicious circle of simplified landscapes and biodiversity loss

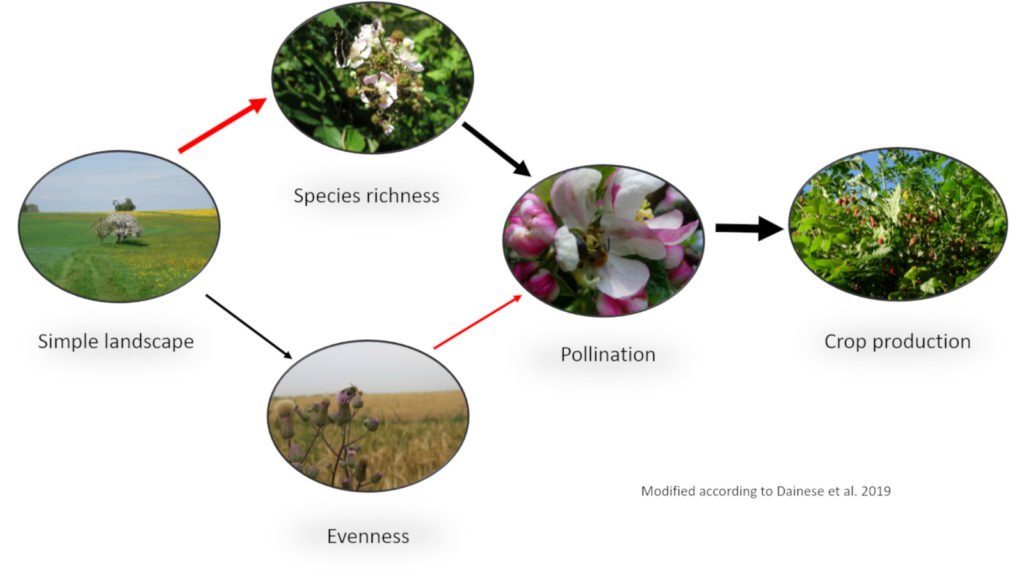

It’s a very common misconception that one pollinator is good for everything. Usually, this pollinator is the Western honey bee. There’s already plenty of research that this isn’t true, that diverse pollinator communities increase pollination success. A group of scientists now analysed 89 studies from 1,475 sites all over the world. And showed that crop production benefits from biodiversity – by increasing the ecosystem services of pollination and pest control. All over these studies, as a common principle, pollination increased crop yields. Pollination, on the other hand, increased by species-rich pollinator communities. And decreased with the evenness of this community increasing. This means that the high dominance of single species like honey bees or common carder bees doesn’t lead to optimal results. Simplified landscapes, finally negatively affected species richness and increased evenness. Therefore, simplified landscapes decrease crop production.

The study showed the same relationships also for natural enemies of crop pests. This creates a vicious cycle. Farmers react to lower production with the means they have: fertilizer, pesticides, extension of agricultural area etc. But there’s a limit for improving with technical measures if the foundation isn’t solid. The name of this foundation: biodiversity. This is a common principle all over these 1,475 sites worldwide. However, how diversity looks like at each site and what measures work best there is different. That’s something to keep in mind: there’s no one-fits-all solution.

Making changes in land use possible

As much as I enjoyed this analysis of the relationship of biodiversity and land use, I missed something. We know WHY we have to change something – but the HOW is missing. Only knowing the why leads to simplifications at another level, like promoting something like flowering strips everywhere. Perhaps even with always the same seed mixes. This doesn’t help biodiversity and isn’t sustainable. If the farmers don’t see an effect that benefits them, they won’t see a sense in trying something different. Politicians will say: we financed this successful project! We care for bees, biodiversity, sustainable agriculture! That’s conservation as an event, activism. Conservationists will be disappointed because it was only the first step and the blaming starts over again. Not very helpful, isn’t it?

Wouldn’t it be better to build up an approach with multiple tiers? We start with what we know, there already are plenty of measures out there. We could use this as a toolbox to choose from. At the same time, scientists monitor the outcome and consultants help the farmers to implement the measures. To do what they can and what makes sense. This will look different for a wheat farmer in Eastern Germany or an orange grower in Sicily. Even for almond orchards in Andalusia or California. All of them will profit from biodiversity but in different ways. The difference to what we’re already doing: monitoring and consultancy. This is what turns activism in continuous effort. It’s nothing new, but it’s not very common.

Land use and habitat conservation at a political level

Conservation needs this continuous effort. In addition, contrary to what the word “conservation” may suggest, it also means change. It means to adapt the measures at each site. Not to impose something on the farmers they don’t want, but to search for the smallest step they’re able and willing to do. And then build up from there. Critics of the last reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in the EU often point out that subsidies should be bound to ecological measures. However, subsidies alone won’t make this change. They’re an important incentive, but if they stand alone, but without consultancy and monitoring this – again – leads to simplification. The same flower strips everywhere.

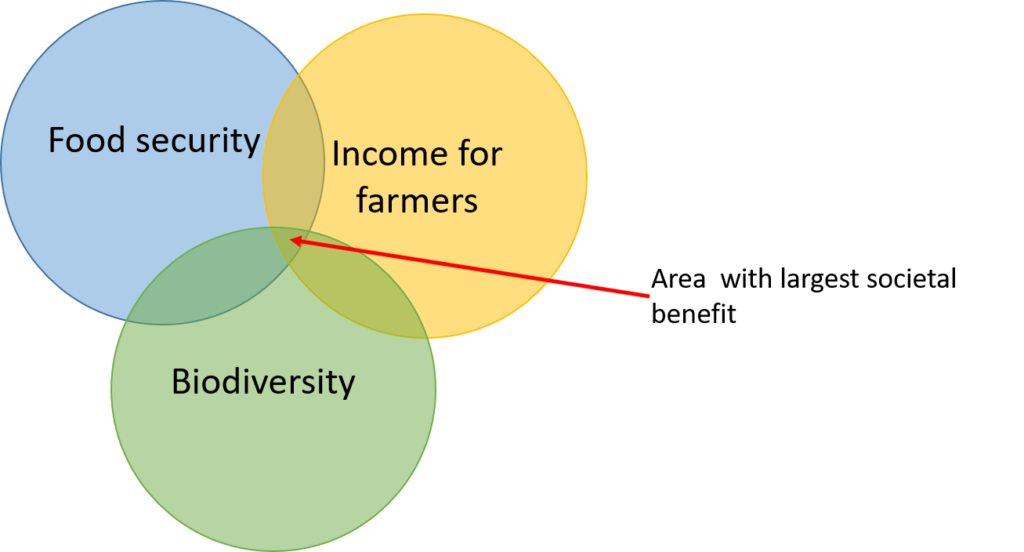

It needs trust, cooperation, and respect to make the change to sustainable agriculture, to more biodiversity. Not simplifying and continuing in doing the same things over and over again. It needs structures that make farmers self-efficient and enable them to make the right decisions. For biodiversity, but also for themselves. Because they will profit from the pollination, the natural enemies of crop pests, of healthy soil and clean water. The CAP should create these structures, in a way that the subsidies will really help to sustain farmers and biodiversity. For the largest benefit for all of us.

This post is part of a series on bees and agriculture. In November of 2020, I discuss four recent papers on the topic. It’s a complex area, much more than you could think hearing the discussions on “save the bees”. Agriculture needs biodiversity, needs pollinators, and, therefore, bees. If you need help in figuring out how this could look like for your association or region, contact me. You can do this over the contact page or follow me on my social media accounts.

I think your description of evenness is wrong. The higher the evenness, the higher the diversity.

The diversity of species in an area depends on both the number of species observed (species richness) and their total numbers, and evenness refers to the relative abundance of species. Evenness is high if all species have similar distribution (i.e., similar population density) (Baker and Savage, 2008).

Please check out the following links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Species_evenness

https://www.researchgate.net/post/What_does_evenness_actually_mean

Thank you for your comment. I discussed the term as I understood it from the paper I’m writing about. The authors of that paper define it that way and I’m discussing the implications of this definition. So maybe another term would be more appropriate for this phenomenon of the dominance of certain species, but in that paper it’s called “evenness” and I stick to that.