My “bee career” began with bumblebees. It was in a course of evolutionary ecology at the university; together with another student I observed different bumblebee species on different flowers in the garden of the faculty. We noticed that some bumblebee species fly on open, more disc-shaped flowers, while other species preferred flowers with long corollas and complex morphology. This observation made us conclude (with some help of the assistant professor), that the first species are short-tongued and the latter long-tongued. These observations and deductions made us understand the concept of ecological niches in a much more impressive way than any book could have done.

A year later, I went to Chile and stayed for another year at the University of Concepción in a master program on entomology. My intentions were not related to bees, but I was already hooked by the former experience with bumblebees. Therefore, I immediately noticed these really enormous native bumblebees, Bombus dahlbomii, the only native one in Chile .

Beyond this, one could say that B. dahlbomii gave my life a turn. I was standing with a friend in front of the faculty building, when suddenly something big flew against my head – it was a B. dahlbomii queen. Apparently my head was too hard for her, she fell on the floor, dazed. This poor queen had the bad luck to meet a zoology student’s head, so she found herself in a killing glass to be observed more thoroughly later. Which changed everything: on this queen there were mites. And on these mites there were even more mites. I already knew about phoresy, but hyperphoresy?

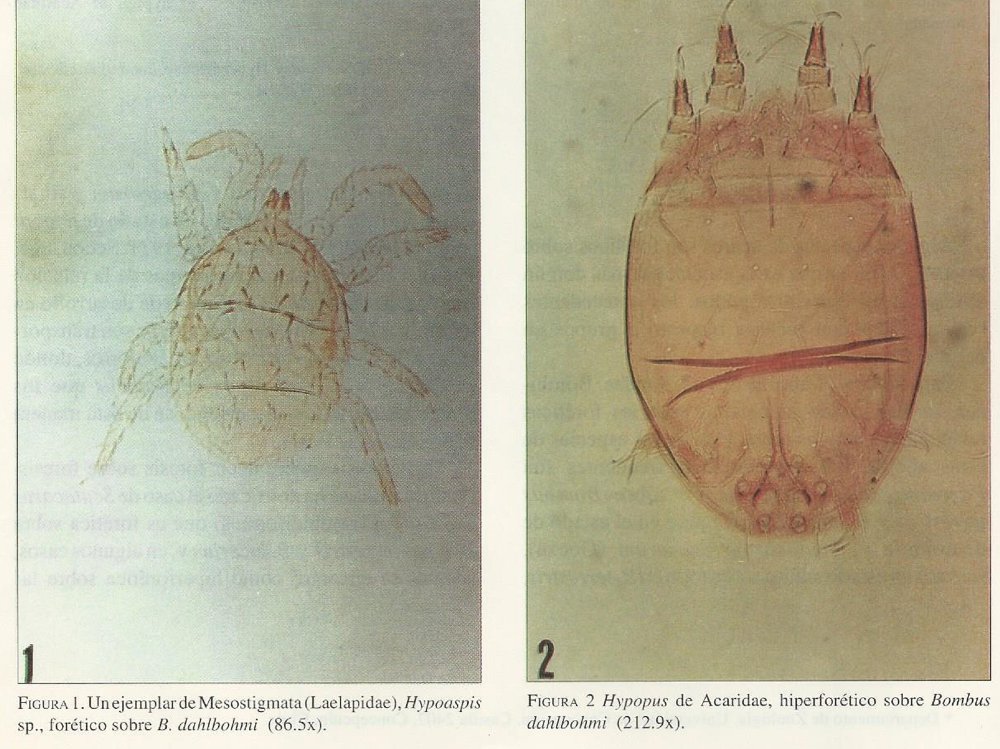

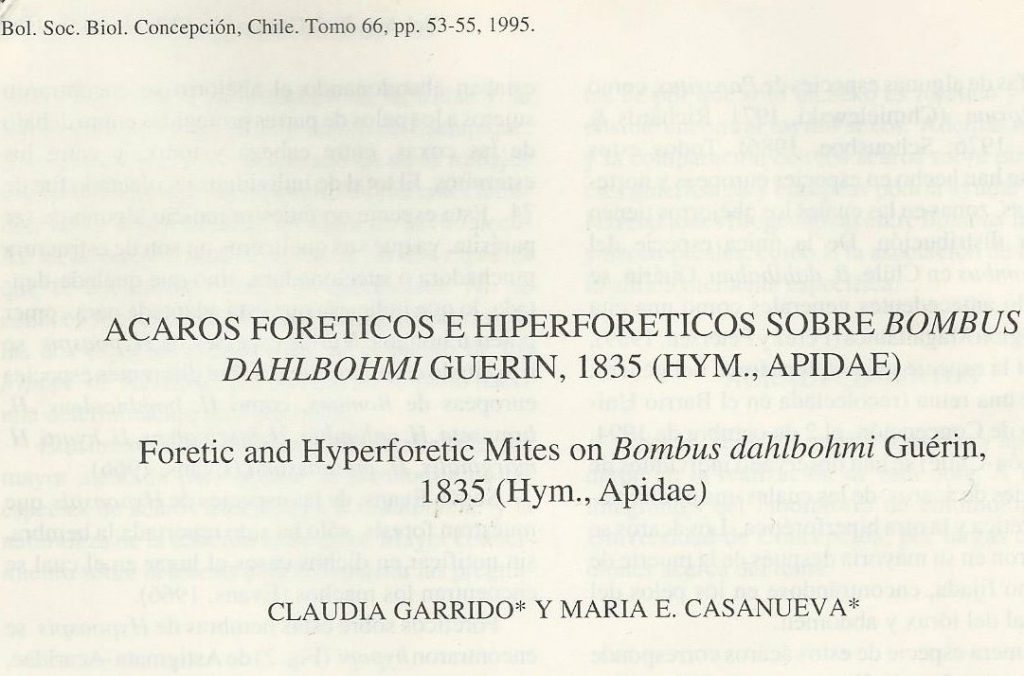

The acarologist in the faculty, María Casanueva, helped me with the determination: the phoretic one corresponded to adults of Hypoaspis sp. (Laelapidae), probably a new species. With the hyperphoretic mites we arrived only to the family level – some immature Acaridae. We even wrote a scientific note in the university’s zoology journal.

This single unlucky bumblebee queen had opened the window to a whole bunch of questions: from the determination and description of the two mite species, over the life-history of these to the phylogenetic relationships of Holarctic and Neotropical bumblebee species and their associated mites. I did not go further into it – I left Chile and its bumblebees after a year – and do not know if anybody else did.

In that times, a European species, B. ruderatus, had already been introduced. They were much less frequent than the native bumblebees and nothing announced the dramatic outcome 20 years later. If B. dahlbomii gets extinct, it is not only a single species that gets lost. It is also all their associated organisms like these two mite species, perhaps even the chance to understand something more of this amazing world we live in. I already commented on other aspects of the introduction of foreign species . But the case of a big, hairy bumblebee, the case of Bombus dahlbomii for me is much more than this: it is personal. I am just terribly sad.

Can you tell me anything about the bombus dahlbomii queen bee behavior in relation to the colony?

Hi Ryan, thank you for commenting. Unfortunately, I don’t have any papers on behaviour of Bombus dahlbomii queens. As bumblebees usually do, queens found a nest alone and provide for the brood until the first workers hatch. The colonies then grow slowly and begin to produce young queens and males in summer. The colony dies in late summer/autumn and only the young queens overwinter. However, the specific rhythms, colony size etc. vary from species to species. I can recommend Bernd Heinrichs book “Bumblebee economics” if you want to learn more about bumblebee biology.

Hi Ryan

There are a few published studies about Chilean bumblebee, mainly distribution and feeding plants.

Nonetheless the life cycle of that species was well studied almost 20 years ago but the information remains unpublished as all of it was protected under a patent.

Hi, thank you for this additional info! And sorry for approving only now. I’m not getting the notifications for some reason.

I have property in the mountains near Pucon. I have observed these native bees in the area. Will the introduction of European honey bees endanger the native bee population?

There’s no data for that. However, we know that honey beestransmit diseases to other bees. Considering the vulnerability of B. dahlbomii, it would be better not to bring honey bees to that area.

Hi Rick

Some evidences have been published arguing that introduced European bumblebees are the main factor for Chilean bumblebee population decline. Mainly due to introduced bumblebee diseases.

Thanks again!

I photographed a very large bumblebee at my home in North Central Washington state in the US. Is it possible that B. dahlbomii found it’s way up here so far from S. America?

Hi Wayne, you have a number of large bumblebee species in North America. It will be one of those. B. dahlbomii is getting extinct and is monitored pretty closely, so any expansion of its range would be noticed. I’m not an expert for North American bumblebees, but there are some nice guides out there you could check (e.g. Bees in your backyard https://www.beesinyourbackyard.com/).