Another paper on the US colony losses entered the discussion – and it brings some important data on the causes of the phenomenon. This one is based on two surveys – one by the Project Apis m. (PAm) and the other by the American Beekeeping Federation. The former had much more respondents and is more detailed, so I’ll stick to the PAm results. For this survey, all kinds of beekeepers were asked – commercial (more than 500 colonies), sideliners (50-500 colonies) and hobbyists (less than 50 colonies). The 842 responses came from all over the USA – so it’s a pretty solid data base.

First and foremost, in this survey beekeepers of all groups named varroa as the main reason for their losses. As I already mentioned last time – not a big surprise. That’s what we see in most monitorings on colony losses. The special thing – again – are the dimensions of losses. I was aware of the higher losses over time in the US compared to Europe. But seeing the number nonetheless shocked me: Long-term losses in the USA have been about 40% over the years. That’s extremely high! In the long-term monitoring we have running here in Germany, the average winter losses are between 10-15%. Everything above that is a reason to look deeper into the causes. And the situation is similar also in other European countries.

Which doesn’t mean that larger losses don’t occur. This year I’m hearing some bad news from Bulgaria, for instance. But consistently around 40%? Something’s going on there.

A more detailed look into the US colony losses

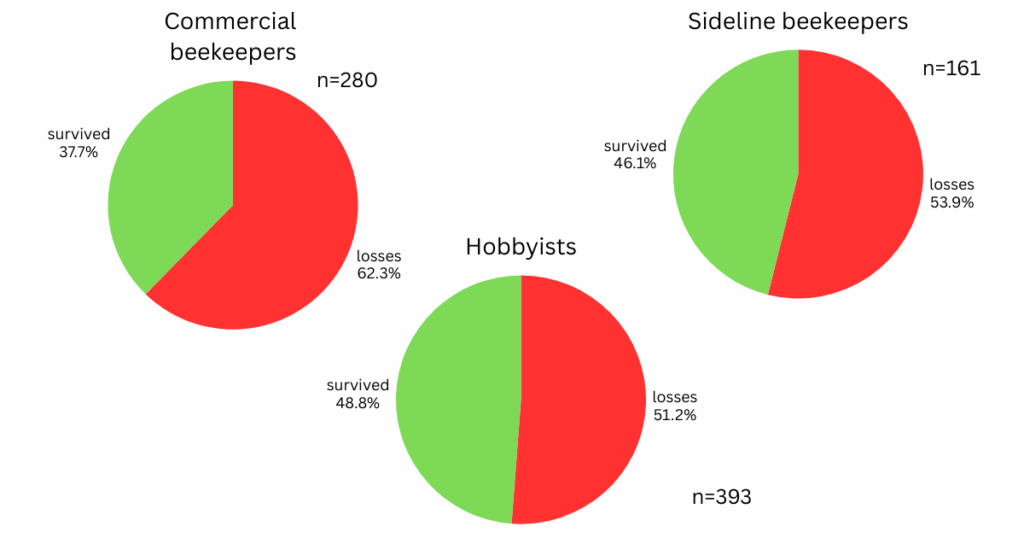

The first interesting result of this survey was that colony losses weren’t the same for professionals, sideliners, or hobbyists. Commercial beekeepers had the highest colony losses – and that’s the number that has been repeated in the media: 62.3% of the colonies died. And with professional beekeepers holding the majority of the colonies, that means more than a million of them dead. Bad thing.

It was also interesting to see that the high losses apparently motivated commercial beekeepers to participate in the survey. In the data I’ve seen in previous years on the Project Apis m website, they were definitely a minority. The surveys usually were answered mainly by hobbyists, followed by sideline beekeepers and only few professionals. So, that’s a sign, too: The situation got so bad, that commercial beekeepers took the time to answer the survey. This is how this looked like:

Mean colony losses in the different groups of beekeepers. n=number of beekeepers who answered the question on their losses – not everyone answered all the questions.

Now it gets really interesting, especially concerning the paper I discussed last time: The losses did not (NOT!) relate to the use of amitraz. Though it is widely used between commercial beekeepers, treating with amitraz or something else did not influence the colony losses. This confirms what I said in my previous post: The claim that amitraz resistance was not supported by this survey. In my opinion, that claim was a massive overinterpretation. I discussed that in detail in my previous post.

Some, let’s say, strange practices

Commercial beekeepers used mostly amitraz and oxalic acid, while the other groups also used thymol and formic acid. This is something we see also in other parts of the world: The more colonies you have, the more you go for the faster methods of treating against varroa mites.

Something else caught my eye, though. And, honestly, shocked me. In addition to the question what substances were used for the treatment, the survey also asked for the frequency. So, how many times do you treat against varroa? Well, I expected that there would be some who said never. Especially among the hobbyists. But it was the other extreme that was… disturbing. There were single hobby beekeepers who treated more than 20 times. Twenty. Sorry, but can somebody explain?

This was the extreme, obviously. But also the mean values didn’t show an understanding of what treatments are about: Hobbyists treated on average 2.1 times. Which means that many, many of them didn’t treat at all to reduce the mean so much despite of those 20 times a year of the other end. Sideline beekeepers treated on average 3.5 times a year, and commercial beekeepers 4.7 times. So, the more dependent a beekeeper was on their colonies for their income, the more often they treated. But all of them neglected the main principle of varroa treatments. Of medical/veterinary treatments in general:

As much as necessary, as little as possible.

It’s not about “the more, the better”, as some seem to think. It’s about using medicines correctly. Because, repeat after me:

Varroa treatments are veterinary medicine.

And every medicine has side effects. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t have the desired effect, too. So, treatments are ALWAYS about the balance that you kill varroa mites, but not your colonies.

Again: what consequences do we draw from the US colony losses?

To be honest, I’m flabbergasted. Only this little detail is enough to explain the high losses. Bee health, low colony losses (in the USA or elsewhere) need educated beekeepers. And these numbers, this survey shows an extent of missing education that I definitely didn’t expect. I’m sorry for my little diplomacy here, but sometimes things just have to be said.

And I don’t blame beekeepers alone for this. There are always those who need the education and those who educate. Or teach. The persistent high colony losses in the US show that the knowledge transfer was… scarce to say the least. It’s not enough to do the research, dear colleagues. If you’re talking about solutions, the data alone don’t help the practitioner. They need to know how to apply these data to their daily practice. It’s not done with publishing papers. That’s good for you, not necessarily for the beekeepers if they don’t know how to do things.

So, what consequences do we draw from the US colony losses? Especially high this year, but concerning also in previous years? What happened since 2007 or whenever CCD was first described? Why didn’t the situation improve? Don’t get me wrong, single years with extreme mortality, ok, that would be acceptable. As long as the general tendency goes in the right direction. This wasn’t the case. Why? What are the structural issues that have to be addressed for getting the job done?

This, again, applies to the different levels of responsibility. Individuals have to educate themselves. Communities must offer education (scientists, associations…) and make it applicable for the real practice. As a help for developing a varroa treatment strategy, I wrote this some time ago. Search for “varroa” on this blog, you’ll find a lot. If you have questions, leave them in the comments below. Just crying for new treatments won’t change anything.

Finally, there’s the third level of responsibility: The political level. They have to make sure, that everyone gets the education they need. Education, for beekeepers and whoever, is the very foundation of informed and mature citizens. So, citizens that can take their responsibility. And it’s the community level that has to ask – and fight – for it.

Rant over.

P.S.: There’s much more in this paper that I would like to discuss, like supplementary feeding. This also relates to bee health and good practices. But it’ll have to wait for another time.