People often ask me why we need so many bee species. There’s the honey bee, right? If you follow this blog for a while, you may imagine my answer. That honey bees can’t do it all alone. I usually talk only about bees, but some of my recent activities made me read Jeff Ollertons review on pollinator diversity again. Pollinators are much more than bees: there are about 20,000 species of bees in the world and 350,000 if we take all (known) pollinators. Those include insects, but also birds, mammals and who knows what other animals. We still don’t know them all. Almost everybody knows honey bees (at least that they exist), but only few people know about fig wasps. But does the fact that we “know” something make it most important or “the best”?

Bees aren’t the most diverse pollinators

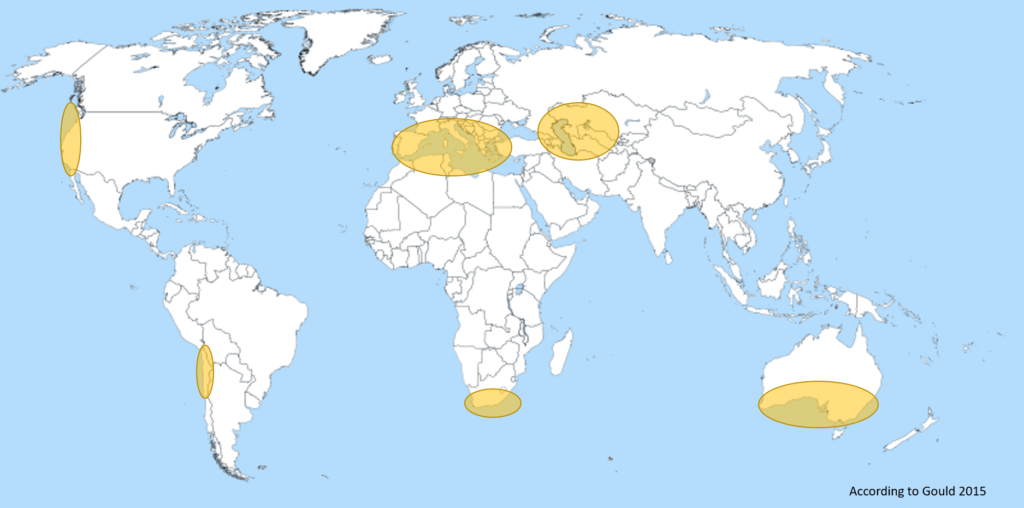

Let’s stay with the bees at first to develop this question. Bees rely on flowers both as adults as during their development. They have special anatomic features to collect pollen, for example their feathery hairs in which pollen grains attach easily. This makes them good pollinators. Bees and flowers seem to be the ideal pairing. However, bee diversity doesn’t match with plant diversity. Look at this:

Bee hot spots, i.e. regions with highest diversity, are in areas with Mediterranean climate. But only relatively few bee species live in the tropics. The original map and some more information here.

The highest diversity of bees isn’t where plants are most diverse, in the tropics. Bees like it warm, but dry, like in the Mediterranean. Tropical plants flower, too, of course. But there are less flowers of the kind bees prefer. Only by this piece of information it should be clear that bees aren’t “the most important pollinators”. And if 20,000 species aren’t, how could a single species – European Honey Bees – take this role?

Are we asking the right questions?

This of course leads to the question which are the most important pollinators. But this isn’t the right question, it depends on the perspective. For us, European Honey Bees are very important because they play a large role in crop pollination and produce honey. But for a fig tree or a yucca palm, honey bees or even other bees aren’t at all important. They rely totally on fig wasps or on nocturnal moths. Considering pollinator diversity, moths and butterflies with more than 140,000 flower visiting species represent the largest group.

Let’s do a thought experiment: imagine a beautiful nocturnal moth as honey producer instead of honey bees. For ages, this honey has been the only accessible sweetener for people and they learned how to manage this moth in the moon light. If such a moth would exist, wouldn’t we consider them the most important pollinators? This comparison is kind of awkward, but it illustrates my point: we consider mainly what we know, what relates to us. I’m a bee person, and that’s why I talk mostly about bee diversity and not pollinator diversity in general. But this is because I prefer not to talk about things I don’t know well. Not because other pollinators aren’t important.

Consequences for conservation

This bias to honey bees has serious consequences for conservation, as pointed out only last week in Science. Honey bee colonies usually are crowded in apiaries and reach high densities in mass flowering crops. Because of their high abundance, they can out-compete wild bee species and spillover also to natural areas. Which again reminded me of something:

Echium meadow, an alien plant in Chile and full of honey bees, also an alien species. This was in the Andes, and I was in there searching for native bees.

In 1994, I was studying in Chile for a year and went on excursion with some other students. We were in a still populated area of the Andes, but not in highly intense agricultural landscape. I had just discovered the incredible bee diversity in the entomological collection of the zoological faculty in the University of Concepción. So during this trip I wanted to stop at every flower and look for bees. This meadow seemed paradise to me, until I noticed that the flowers weren’t native (Viper’s bugloss, not native at all). But still, the meadow was buzzing. And then the next disappointment: all honey bees.

I wasn’t in a protected area, there was agriculture, but scattered with natural habitat. However, I didn’t see any native bee in this meadow. This dominance of managed honey bees can harm wild pollinators. But again, this depends on many factors. I don’t want to demonize honey bees, it’s not them or non-managed pollinators. But, talking about pollinator diversity and conservation, honey bees aren’t the right model to look at.

Pollinator diversity for ecosystem stability

Which brings me again back to the question why there are so many pollinators. There is a certain pollinator redundancy, as Ollerton points out in his review. About 350,000 pollinator species take care of 352,000 flowering plant species. We still don’t know all pollinator species (especially the nocturnal ones…), so there may be many more. There are also very specialized relationships between plants and their pollinators, like the already mentioned fig and fig wasps. Or very generalistic (polylectic, remember?) ones, like honey bees and the flowers they visit. Often there are several pollinators that visit a single plant species. On the other hand, a single pollinator species may feed on only few plants for pollen but drink nectar from a larger variety.

This web of pollination systems is necessary for ecosystem stability. This shows also in agricultural landscape: in intensely managed regions the loss of wildflowers and, therefore, also wild pollinators creates the need to bring in high numbers of managed honey bee colonies. It’s a kind of vicious cycle. The loss of plant diversity through land-use change is one of the major drivers for pollinator loss. Which again intensifies the pollination crisis in agriculture.

So no, honey bees aren’t neither the most important pollinators nor can they do the job alone. We need pollinator diversity, also for our very own needs.