The so-called “Krefeld study” brought insect declines into public attention. After Hallmann and co-workers published their results in late 2017, the media were full of scary “insect apocalypse” and similar headlines. Without always doing the subject favour, in my opinion. This 27-year monitoring also got many critics. Sometimes justified, sometimes… not that much. Overall, the results got simplified into bold statements very often, not always helping the discussion.

On a discussion round last September, I was asked, “why scientists haven’t warned the public before”. Well, they did. I’m having discussions about conservation and the importance of insects (or biodiversity in general) for about 30 years now. I dare to say that every ecologist discusses this over and over for a long time already. Now there’s this public awareness; something in the Krefeld study hit the sweet spot of public attention. In consequence, the German Ministry for Environment is funding the Entomological Association in Krefeld for continuing their work. There’s also a national action programme for insect conservation etc. Which is definitely a good thing, though only a starting point.

Another long-term monitoring

The Krefeld study isn’t the only long-term monitoring on insect declines. There were other studies before. Two weeks ago, another long-term monitoring on insects came out, filling some gaps and giving some more details. This monitoring is part of the “biodiversity exploratories”, a large research platform in Germany. It deals with a large array of different questions regarding biodiversity. The arthropod monitoring (insects and spiders) is a core project in this programme. The main question was how agriculture and forestry affect the arthropod fauna in grassland and forests. The sampling sites were in natural reserves as well as in the agricultural landscape.

This monitoring had a different approach than the Krefeld study. It addressed the effects of a gradient of land-use on biodiversity. Most importantly, the landscape level, i.e. the surroundings of the sample sites were included as well. This gives important additional information: sample sites, like everything, aren’t isolated from the rest of the world. This will be important, later on.

The scientists worked in three different regions in Germany: in the Southwest (Schwäbische Alb), in Central Germany (Hainich) and in the Northeast (Schorfheide-Chorin). In these areas, they studied 150 sites in grassland and 30 sites in forests in a ten-year period (2008 and 2017). In addition, they draw circles around these sites with a radius up to 2km. By this, it was possible to analyse the effect at a landscape level.

Going a step further to the Krefeld study

The Krefeld study analysed the biomass of the samples, without determining the insects. In the “biodiversity exploratory”, the investigators confirmed the order of magnitude: they found an average decline of 67% in the biomass – but only in grassland. In forests, the decline was “only” 41%. This is interesting because it confirms the observation that open landscapes are more affected than forests.

In addition to the biomass, the biodiversity exploratories also analysed the total species number in the samples and the abundance of these species. In all cases confirming the decline. The most interesting part of this monitoring, however, in my opinion, is the division into different trophic guilds. This means they divided the insects and spiders in the samples in herbivores, omnivores, myceto-detritivores (i.e. eating fungi and dead organic material) and carnivores. This classification indicates the effect on an ecological function, not only on a list of species. Interestingly, this showed to be important: in grassland, the only group in which the declines weren’t significant were the carnivores. So, apparently, the factors causing the declines still didn’t “climb all the way up” to the higher trophic levels. However, in forests, the situation was different and more complex: herbivores increased in abundance and species number. On the other hand, other trophic guilds declined.

Differences between grassland and forests

While the Krefeld study didn’t get any data for the influence of the surrounding landscape, the biodiversity exploratories did. The results for grassland are in the same order of magnitude as the monitoring from the entomologists in Krefeld. In forests, the decline is less marked in more complex. This shows well in the abundance data: in grassland, both abundant and less abundant species declined. However, species disappeared mainly if they were already rare. The total abundance declined by 78%. In forests, the overall abundance decreased by 17%, which isn’t significant. Less abundant species decreased further, while some of the most abundant species increased. This shifts the “dominance” in the insect communities of the forests. The consequences of this shift in community composition aren’t clear yet, it wasn’t discussed in the paper.

Considering the causes of insect decline, the biodiversity exploratories clearly show that there is no easy answer. Insects declined independently of the intensity of management of the local sites. The researchers themselves don’t want to name a “main suspect” for the declines. Yet, they point out the role of agriculture. That is arable land. The more fields were around the grasslands, the more the insects declined on these sites. In forests, again, the picture was more complex. Species that remained during their whole life span in the forest declined less than those, which also get out on the open landscape.

Pesticides and other factors

The easiest conclusion would be to think that pesticides are reducing insect fauna. And of course, I can’t say that this isn’t true. Many pesticides are designed to kill insects after all. However, as I mentioned before, even the authors of the biodiversity exploratories don’t want to name a single factor as the main reason for the decline. The data show a far more complex situation. Great portions of arable land also mean very homogenous landscapes, which means less insect habitat. Fertilizers carry nutrients into the surrounding landscape as well. This changes the plant communities, which in turn affects insects. In addition, orchards are also treated with pesticides, but the influence is from “arable land”. I don’t know if this is because there were no orchards in the study areas or if there wasn’t an effect.

As you know, I don’t like simplifications. Pesticides surely are contributing to insect declines. However, if we focus only on a single factor, we don’t solve the problem. Banning all pesticides could bring some relief, but it wouldn’t “save the insects” if the habitat structure etc. doesn’t improve. The first and most important measures, in my opinion, relate to conserving and restoring habitat. Many studies show that this has a huge effect on biodiversity in the agricultural landscape. It’s a much more complex task than banning pesticides. Which is difficult enough.

Yet, the numbers are concerning. “In such a short time-frame, we shouldn’t have seen any change.” said Wolfgang Weisser, chair of the terrestrial ecology at the Technical University in Munich and co-author of the study, in an interview with the German journal “Die Zeit”. Ten years aren’t that long after all. They observed the strongest declines between 2008 and 2010. Since then, the declines are slower, but not stopped.

Consequences for conservation and agriculture

As always, data are only a first step and add to the knowledge on how to stop the declines. Or at least to further slow them down. The biodiversity exploratories clearly show the effect of the surrounding landscape. The authors conclude that land-use policies should change for improving habitat for insects at a national and international level. In Europe, this is currently very relevant: the common agricultural policy (CAP) is about to change in 2020. By the information I have the changes don’t go in the right direction. Without going into detail of the CAP (complicated stuff, I can tell…): the adapted, regional measures will get less money. This already is a point of discussion and critics.

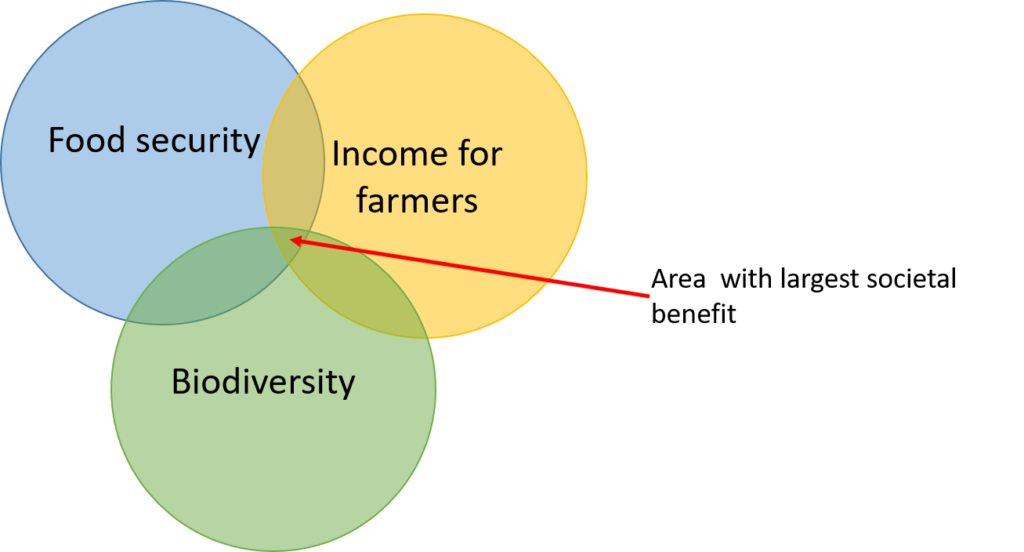

Despite the public interest and all the discussions about biodiversity decline, apparently the importance still doesn’t arrive in the EU. In my opinion, I think it’s important to make clear that biodiversity, farmers’ income and food security are strongly connected. In the end, it’s all about to increase that “sweet spot” between these areas. It’s the area of the largest societal interest. And that should be the interest of the EU for their citizens. In this topic, it’s like with the climate crisis: it would be time to listen to the scientists.

Whilst I accept the significance of habitat loss and theserious impact of pesticides, there is never a mention of any potential impact of non ionizing radio frequencies, that are increasing day by day.

The impact of total global saturation of satellite transmissions at ghz frequencies has not been assessed and may have the potential to wipe out insect life completely.

Thanks for your comment. However, in science, there’s the principle of parsimony. Meaning that the simplest explanation usually is the most probable. Simple in this case meaning that it should contain variables that are in a logical relationship to each other. Scientific evidence does not show any impact of radio frequencies, while we have more than enough evidence for the impact of habitat loss.